Climate Change Mitigation: Strategies for a Sustainable Future

The need to deploy efficient mitigation techniques becomes more and more obvious as the effects of climate change on our planet worsen. These tactics aim to increase the ability of carbon sinks to absorb greenhouse gases (GHGs) while reducing their emissions into the atmosphere. Climate change mitigation covers a broad range of strategies meant to guide us toward a more sustainable future, from switching to renewable energy sources to encouraging energy efficiency and reforestation programs.

Climate Change Mitigation: Navigating Towards Sustainability

Understanding the Essence of Mitigation

Climate Change Mitigation: A Transformative Imperative

Central to the global response to climate change is the imperative of mitigation, a multifaceted strategy aimed at curbing the relentless march of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. This strategy hinges on a profound objective: achieving a net-zero level of GHG emissions by 2050. This resolute target, championed by the esteemed Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), resonates as the rallying cry for nations worldwide, encapsulating the urgency and gravity of our shared responsibility.

Altering the Course of Global Warming

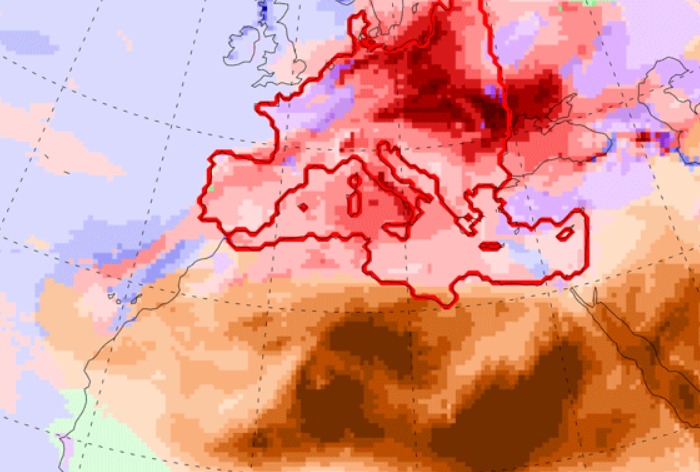

The essence of mitigation is not merely an academic exercise; it embodies a collective endeavor to reshape the course of global warming. As the earth’s temperature continues its upward trajectory, the ramifications for our environment, societies, and economies become increasingly dire. The focal point of mitigation is to reverse this trajectory, to bend the curve of emissions toward a sustainable equilibrium. By orchestrating a synchronized reduction in GHG emissions and augmenting the capacity of carbon sinks to absorb these emissions, humanity aims to recalibrate the balance between progress and preservation.

Charting a Sustainable Future

The raison d’être of mitigation extends beyond the confines of policy chambers and scientific debates. It resonates as a clarion call for sustainable action, an imperative that transcends borders and ideologies. To achieve this, it demands a comprehensive overhaul of energy systems, industrial practices, and societal norms. It beckons governments, industries, and individuals to collaborate on an unprecedented scale, pivoting toward renewable energy sources, revolutionizing transportation, and embracing circular economies. Each act of mitigation is a step toward harmonizing our advancement with the delicate ecosystems that sustain us.

Mitigation’s Multidimensional Impact

Mitigation is not a monolithic solution; rather, it is a multidimensional tapestry woven with diverse threads of action. From transitioning to renewable energy sources to bolstering energy efficiency across sectors, the spectrum of mitigation strategies is as vibrant as it is essential. Reforestation emerges as a pivotal endeavor, creating verdant carbon sinks that capture atmospheric CO2. The synergy of these strategies crafts a roadmap toward sustainability, where emissions are diminished, and the planet’s capacity to absorb CO2 is amplified.

Understanding the Essence of Mitigation

Climate Change Mitigation: A Transformative Imperative

Central to the global response to climate change is the imperative of mitigation, a multifaceted strategy aimed at curbing the relentless march of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. This strategy hinges on a profound objective: achieving a net-zero level of GHG emissions by 2050. This resolute target, championed by the esteemed Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), resonates as the rallying cry for nations worldwide, encapsulating the urgency and gravity of our shared responsibility.

Altering the Course of Global Warming

The essence of mitigation is not merely an academic exercise; it embodies a collective endeavor to reshape the course of global warming. As the earth’s temperature continues its upward trajectory, the ramifications for our environment, societies, and economies become increasingly dire. The focal point of mitigation is to reverse this trajectory, to bend the curve of emissions toward a sustainable equilibrium. By orchestrating a synchronized reduction in GHG emissions and augmenting the capacity of carbon sinks to absorb these emissions, humanity aims to recalibrate the balance between progress and preservation.

Charting a Sustainable Future

The raison d’être of mitigation extends beyond the confines of policy chambers and scientific debates. It resonates as a clarion call for sustainable action, an imperative that transcends borders and ideologies. To achieve this, it demands a comprehensive overhaul of energy systems, industrial practices, and societal norms. It beckons governments, industries, and individuals to collaborate on an unprecedented scale, pivoting toward renewable energy sources, revolutionizing transportation, and embracing circular economies. Each act of mitigation is a step toward harmonizing our advancement with the delicate ecosystems that sustain us.

Mitigation’s Multidimensional Impact

Mitigation is not a monolithic solution; rather, it is a multidimensional tapestry woven with diverse threads of action. From transitioning to renewable energy sources to bolstering energy efficiency across sectors, the spectrum of mitigation strategies is as vibrant as it is essential. Reforestation emerges as a pivotal endeavor, creating verdant carbon sinks that capture atmospheric CO2. The synergy of these strategies crafts a roadmap toward sustainability, where emissions are diminished, and the planet’s capacity to absorb CO2 is amplified.

Uniting Uniting for a Common Purposefor a Common Purpose

In the face of a warming world, mitigation stands as a testament to humanity’s capacity for unity and innovation. It channels the collective determination of nations to transcend the boundaries of self-interest and embrace the shared fate of our planet. The global community’s commitment to mitigation rests not merely on political rhetoric but on the tangible actions undertaken to reduce emissions. As industries pivot, as governments legislate, and as individuals adopt sustainable lifestyles, the essence of mitigation finds embodiment in every stride toward a resilient and thriving future.

Tracing the Evolution of Mitigation under UNFCCC

With its roots in the pledges made by countries under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), climate change mitigation is a key component of global climate action. In order to lessen the effects of climate change, Parties to the Convention vowed to put in place a variety of measures, including regulations, incentives, and investments in various sectors. These initiatives aim to tackle the difficult problem of climate change by decreasing GHG emissions while also enhancing carbon sinks.

The Kyoto Protocol, adopted in 1997, marked a pivotal milestone by establishing binding emission reduction targets for industrialized nations listed in Annex I of the Convention. This protocol introduced differentiation between developed and developing countries, with the former setting caps for emissions across all economic sectors and the latter focusing on implementing targeted programs and projects.

Unveiling the Kyoto Protocol’s Mechanism

The Clean Development Mechanism (CDM), a crucial element of the Kyoto Protocol, introduced a pioneering global environmental investment scheme. The CDM enables developed countries and corporations to execute emission reduction projects in developing nations, thereby generating certified emissions reductions (CER) units that can be traded. While designed to promote sustainable development, the CDM has faced scrutiny due to structural challenges and associations with human rights concerns.

The Paris Agreement: A New Horizon for Mitigation

The Paris Agreement, a watershed moment in global climate diplomacy, sets forth a collective ambition to limit global warming to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels, with efforts aimed at achieving a 1.5°C target. This agreement crystallizes the principle of equity, recognizing that developed and developing countries possess disparate capacities and responsibilities in addressing climate change.

To operationalize the Paris Agreement, nations articulated their intended nationally determined contributions (INDCs), outlining their strategies to reduce emissions and enhance resilience. However, these contributions varied widely in scope and methodology due to the absence of harmonized guidelines during their formulation.

Recent Strides and Future Trajectories

Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) were intended to be defined by common standards in recent climate conferences, such as COP24 and COP25. In order to establish a balance between aspiration and reality, these criteria covered substance, structure, and duration. Accountability, openness, and understanding served as the foundation for these conversations, which resulted in choices about NDC accounting and standard timetables for their updating.

The Paris Agreement’s need to establish a public NDC registry provides a clear platform for countries to track their contributions and advancement. Nations struggle with the delicate balance between ambition and practicality, keeping with the broader goal of sustaining a reduction in atmospheric emissions. Scenarios range from 5-year NDCs to suggested 10-year action plans.

Charting the Path Forward

The pursuit of climate change mitigation unfolds as a symphony that knows no boundaries or biases, demanding a harmonious orchestration of global efforts to forge a sustainable destiny. The intricate choreography of mitigative endeavors, the augmentation of carbon sinks, and the intricate interplay of international accords illuminate the multifaceted nature of tackling a challenge that knows no borders. Amidst this intricate dance, nations tread a labyrinthine course of climate action, with the role of mitigation emerging as the North Star that guides the collective resolve to steward our planet for the progeny of tomorrow.

The Role of Differentiation in Climate Change Mitigation

The principle of differentiation recognizes that developed and developing countries have distinct responsibilities and capacities in addressing climate change. This principle, enshrined in the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), guides mitigation efforts by acknowledging the diverse contexts of nations. It underscores the need for more specific guidelines and binding targets for developed countries while granting developing nations greater flexibility.

The Paris Agreement and Differentiation

Enshrined within the tapestry of the Paris Agreement is a profound acknowledgment, guided by the pillars of equity and the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities (CBDRRC). This pivotal accord underscores the imperative for developing nations to embark on a trajectory towards encompassing emission reduction or containment targets that span the breadth of their economies. This recognition is a testament to the nuanced landscape of varied financial resources, technological capabilities, and economic dynamics that uniquely define the realms of developing countries.

Critics and Supporters of Differentiation

While the principle of differentiation is seen as essential for equitable climate action, it has its critics. Some argue that it may limit ambitious climate action, potentially slowing down progress towards mitigating climate change. Nevertheless, differentiation remains integral to the climate justice framework, aiming to create a climate regime based on equity and fair effort sharing.

Recent Developments in Climate Change Mitigation

The latest chapters of climate summits have unfurled a narrative characterized by consequential dialogues and pivotal resolutions in the realm of climate change mitigation. These deliberations have coalesced around crucial facets of national undertakings, their temporal contours, and the establishment of an open ledger dedicated to monitoring and evaluating the trajectory of progress.

Accounting for Parties’ NDCs

Within the realm of COP gatherings, a resolute directive has emerged, stipulating that Parties are obligated to meticulously incorporate their nationally determined contributions (NDCs). This tenet is underscored by the pragmatic mandate to adhere to precise guidelines nestled within annex II. The crux of this deliberation rests upon nurturing clarity, engendering transparency, and fostering comprehension (CTU) in relation to the intricate dance of anthropogenic emissions and the act of sequestration that mirrors the contours of NDCs.

Common Time Frames for NDCs

Agreement on common time frames for updating or communicating NDCs has been an ongoing challenge. Parties with 5-year NDCs are requested to communicate new NDCs by 2020, while those with 10-year NDCs are asked to update by the same year. Resolution of this issue is expected by 2023 during the first global stocktake.

The NDC Registry

Nationally determined contributions are recorded in a public registry, as stipulated in the Paris Agreement. This registry, publicly available and managed by the UNFCCC secretariat, offers transparency while awaiting finalization of modalities and procedures.

Article 6 and Overall Mitigation: A Complex Endeavor

The discourse that enveloped COP25 orbits fervently around the dimensions of Article 6, weaving a narrative that revolves around the intricate endeavor of safeguarding overall mitigation within the global tapestry of emissions (OMGE). This intricately nuanced territory delves into the realm of preserving a comprehensive reduction in global emissions at large, refraining from the practice of offsetting emissions from one sovereign domain to another. The complexity of this issue ripples with profound repercussions, casting its weighty influence across the panorama of worldwide climate action.

What is the primary goal of climate change mitigation?

The main objective of climate change mitigation is to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and enhance carbon sinks, aiming to curb global warming and its detrimental impacts.

What role does the Paris Agreement play in climate change mitigation?

The Paris Agreement provides a comprehensive framework for global climate action, including mitigation strategies. It aims to limit global warming well below 2°C and encourages countries to enhance their climate ambitions through nationally determined contributions.

How does differentiation impact climate change mitigation?

Differentiation recognizes that developed and developing countries have distinct responsibilities and capabilities in addressing climate change. This principle guides mitigation efforts, acknowledging the diverse contexts of nations.